Fast Imaging Pulse Sequences#

Modern MRI scanning relies heavily fast imaging pulse sequences, primarily echo-planar imaging (EPI) and multiple Spin-echo (RARE/FSE/TSE) methods. These allow for multiple k-space lines to be acquired within a single TR.

Learning Goals#

Describe how images are formed

Describe how data is acquired in FSE/TSE sequences

Describe how EPI works

Understand what “spoiling” means

Understand the most popular pulse sequences and their acronyms

Describe how FSE/TSE sequences work

Describe how EPI works

Describe how fast gradient-echo sequences work

Manipulate MRI sequence parameters to improve performance

Understand how and when to accelerate with FSE/TSE

Understand how and when to accelerate with EPI

Understand how contrast changes in fast gradient-echo sequences

Identify artifacts and how to mitigate them

Identify FSE/TSE artifacts include T2 blurring

Identify EPI artifacts including distortion and T2*

Identify fast gradient-echo artifacts such as banding in bSSFP

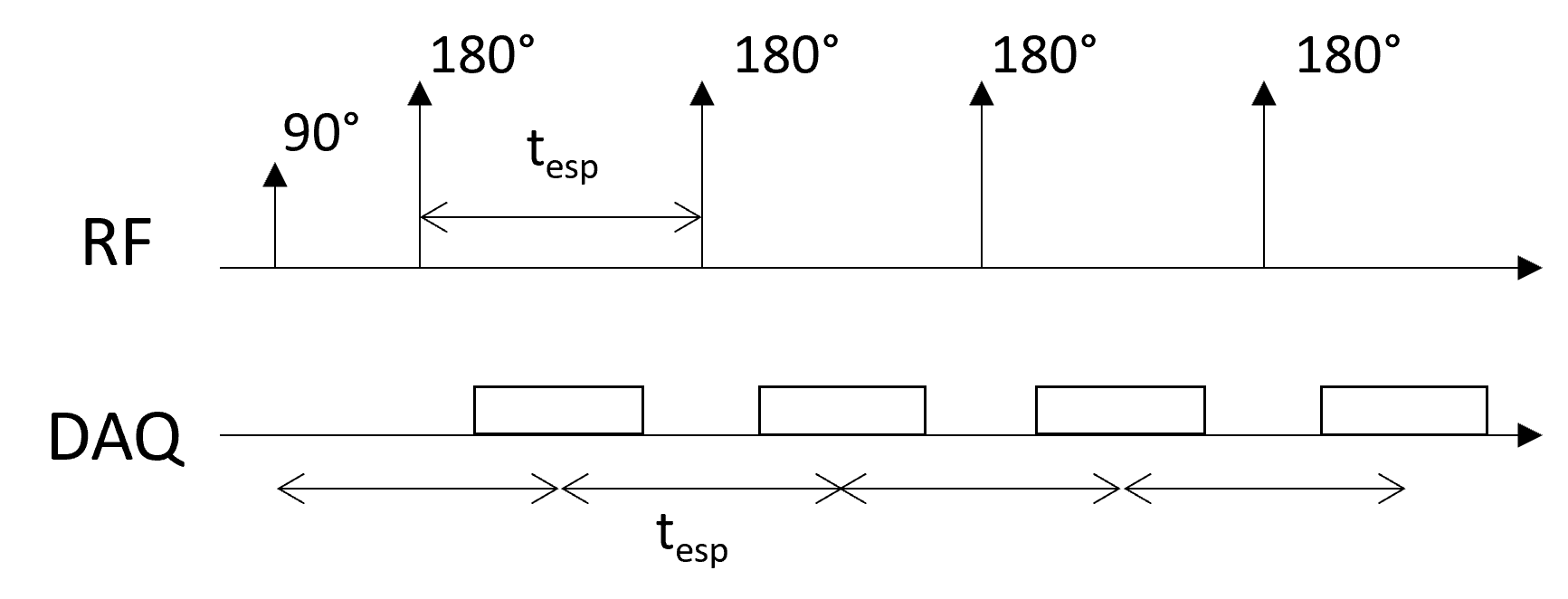

Multiple Spin-echo Sequences (RARE/FSE/TSE)#

These pulse sequences use multiple spin-echo refocusing pulses after a single exictation pulse to acquire multiple k-space lines to be acquired during the multiple spin-echoes that are formed. This technique was originally called Rapid Acquisition with Relaxation Enhancement (RARE), and is known on various MRI scanners as fast spin-echo (FSE, GE Healthcare), turbo spin-echo (TSE, Siemens Healthineers), or turbo field-echo (TFE, Philips Healthcare).

This is the most common pulse sequence used in clinical practice. This is because it is highly SNR efficient and can also be used to generate multiple contrasts. They are particularly effective for T2 and PD-weighted imaging.

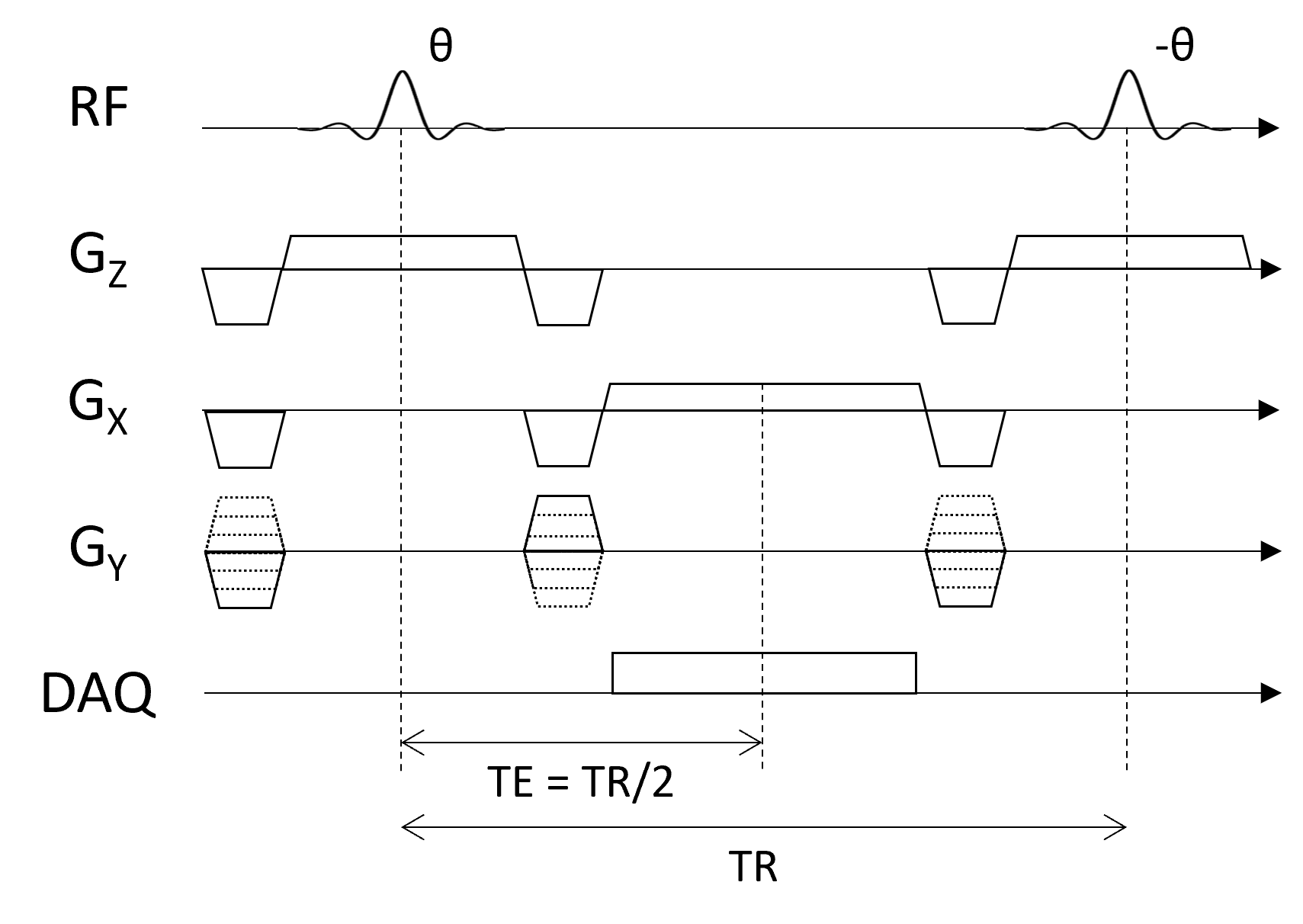

Simplified Pulse Sequence Diagram#

Sequence parameters#

Echo spacing (\(t_{esp}\)) - time between each spin-echo

Echo train length (ETL) - number of spin-echoes with a repetition

Effective TE (\(TE_{eff}\)) - the echo time when the data closest to the center of k-space is acquired.

Tradeoffs#

Pros

Fast

SNR efficient

Supports multiple contrasts by manipulating \(TE_{eff}\)

Cons

Long echo train lengths can lead to T2 blurring or other distortions

High SAR from repeated refocusing pulses

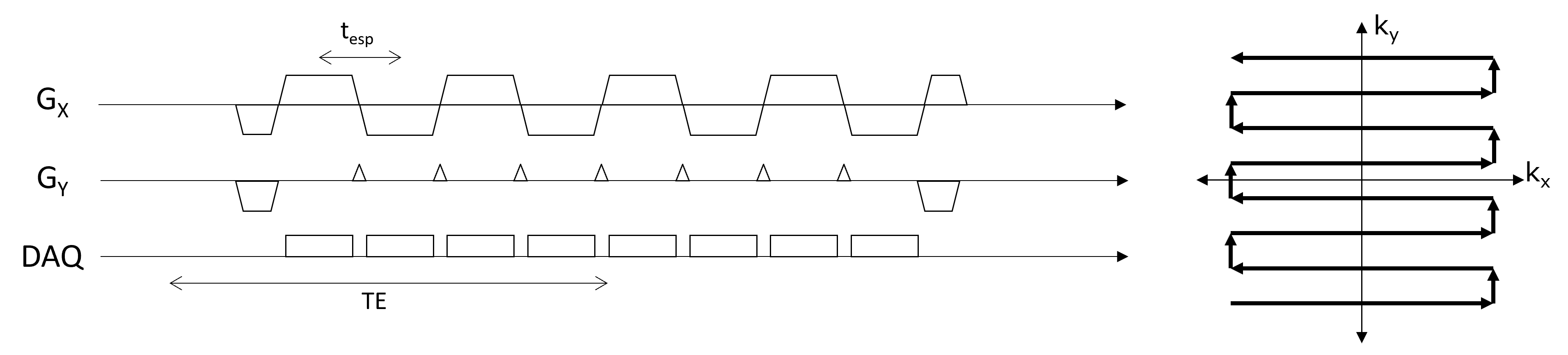

Echo-planar Imaging (EPI)#

These pulse sequences readout multiple k-space lines sequentially for faster imaging. It is commonly used for diffusion-weighted imaging and fMRI.

Pulse Sequence and K-space Diagram#

Sequence parameters#

Echo spacing (\(t_{esp}\)) - time between each readout and gradient-echo

Echo train length (ETL) - number of readouts or k-space lines acquired within a repetition

TE - the time when the data closest to the center of k-space is acquired.

Tradeoffs#

Pros

Extremely Fast, supporting single-shot imaging

Cons

Susceptible to chemical shift and susceptibility displacement artifacts

Sensitive to gradient fidelity artifacts (e.g. Nyquist ghosting)

Long echo train lengths can lead to T2* blurring

Fast gradient-echo sequences#

The basic gradient-echo sequence is typically a spoiled gradient-echo sequence. The sequence is called spoiled because the transverse magnetization is spoiled by a spoiler gradient before the next RF pulse.

Spoiler or Crusher gradients#

A large, unbalanced gradient will create dephasing of the transverse magnetization across the imaging voxels. This effectively eliminates the signal. However, the net magnetization is not truly eliminated, and this can be refocused by gradients.

RF spoiling#

The RF axis of rotation is changed every TR. This reduces the chances of magnetization from previous TRs to become coherently excited. Specific RF spoiling schemes, such as quadratic phase incrementation, is required for this to be effective.

Types of fast gradient-echo sequences#

Spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR)/fast low-angle shot (FLASH)

Aims to full spoil transverse magnetization every TR

Both gradient and RF spoiling are used

Pure T1 weighted contrast

Gradient-recalled acquisition in the steady state (GRASS)/fast imaging with steady-state precession (FISP)

Allows for residual transverse magnetization to be used in the next TR

Refouces frequency and phase encoding gradients

RF spoiling used

Increases T2* contrast

Steady-state free precession (SSFP)/time-reversed fast imaging with steady-state precession (PSIF)

Use gradients to refocus signals from previous TRs

Gradient spoiling but refocused in later TRs

Creates T2/T1 contrast

Balanced SSFP/TrueFISP

Balanced gradients every TR

No spoiling, all magnetization preserved each TR

Creates T2/T1 contrast

High SNR efficiency

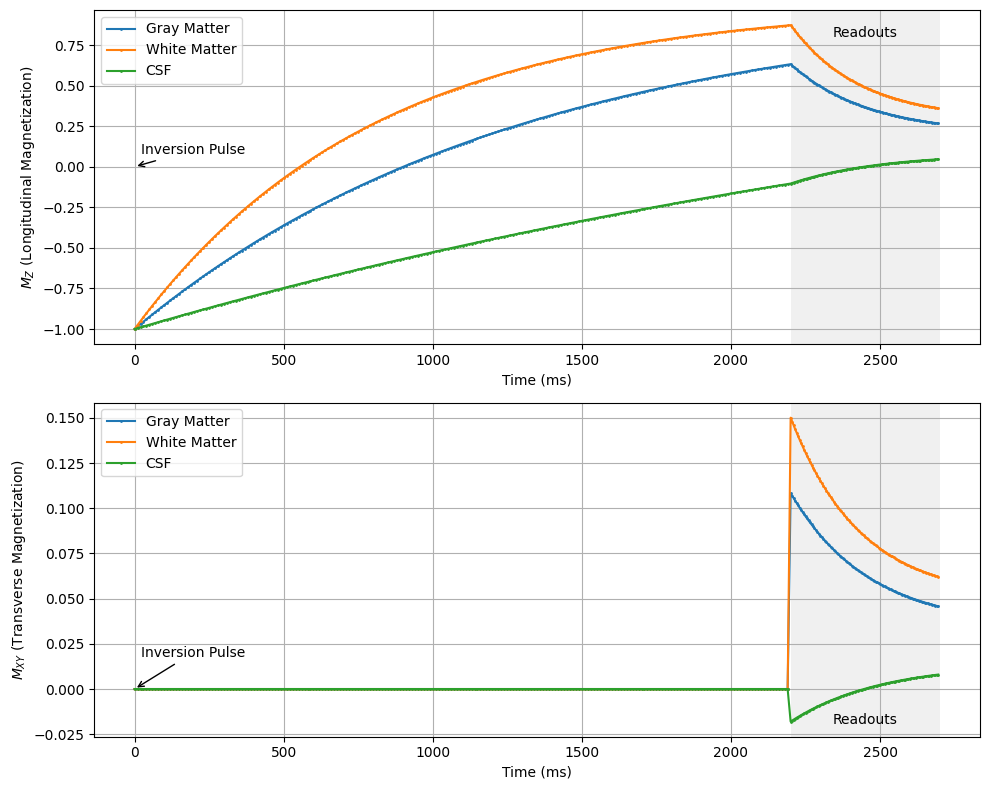

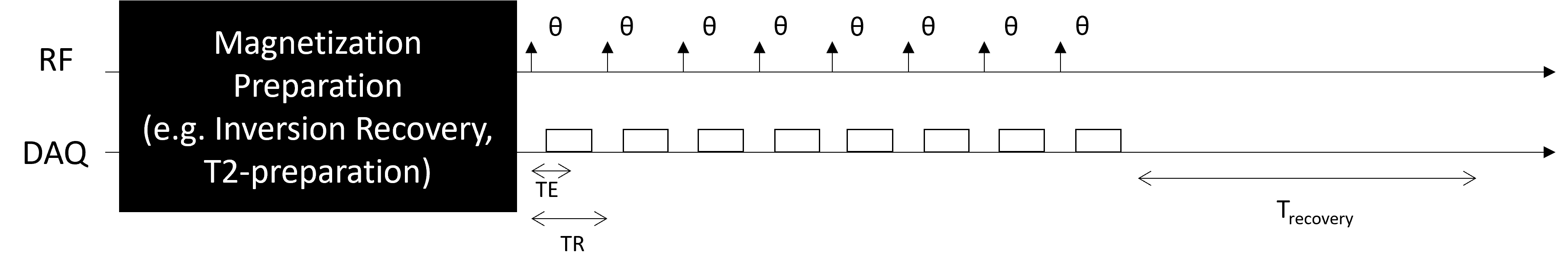

Magnetization Prepared Fast Gradient-echo Sequences#

Magnetization preparation schemes, such as inversion recovery, T2-preparation, and magnetization transfer, encode contrast in the longitudinal magnetization. This contrast can be efficiently imaged with multiple gradient-echo readouts after a single magnetization preparation module.

The most common of this type of sequence is the Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence for brain imaging, which specifically uses inversion recovery magnetization preparation to create T1-weighted contrast, followed by multiple spoiled gradient-echo readouts to retain only T1-weighted contrast.

This sequence includes several additional parameters, including the recovery time, \(T_{recovery}\), and number of readouts per preparation, \(N_{segments}\), as well as the specific paramters of the magnetization preparation.

# Simulate MPRAGE MRI Pulse Sequence, which typically uses inversion preparation

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

flip_angle = 10 * np.pi / 180 # Flip angle in radians

TE = 1 # Echo time in ms

TR = 5 # Repetition time in ms

N_segments = 100 # Number of pulses

T_recovery = 2200 # Delay after inversion pulse in ms

MZ_start = 1.0 # Initial longitudinal magnetization

MZ_inversion = -MZ_start # After inversion pulse

t_recovery = np.arange(0, T_recovery, 10) # Time array for recovery period

t_segments = np.arange(0, N_segments * TR, TR) + T_recovery # Time array for pulse sequence

# Define T1/T2 values for different tissue types

tissues = {

'Gray Matter': {'T1': 1300, 'T2': 80},

'White Matter': {'T1': 800, 'T2': 110},

'CSF': {'T1': 3700, 'T2': 1700}

}

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(10, 8))

for tissue_name, params in tissues.items():

T1, T2 = params['T1'], params['T2']

# Vectorized longitudinal recovery during the inversion recovery period

MZ_recovery = MZ_inversion * np.exp(-t_recovery / T1) + (1 - np.exp(-t_recovery / T1))

MZ_segments = np.zeros(N_segments)

MXY_segments = np.zeros(N_segments)

# Longitudinal magnetization at the start of the segmented readouts

MZ_segments[0] = MZ_inversion * np.exp(-T_recovery / T1) + (1 - np.exp(-T_recovery / T1))

for n in range(1, N_segments):

MZ_segments[n] = MZ_segments[n-1] * np.cos(flip_angle) * np.exp(-TR / T1) + (1 - np.exp(-TR / T1))

for n in range(0, N_segments):

MXY_segments[n] = MZ_segments[n] * np.sin(flip_angle) * np.exp(-TE / T2)

ax1.plot(np.concatenate((t_recovery, t_segments)), np.concatenate((MZ_recovery, MZ_segments)), label=tissue_name, marker='o', markersize=1)

ax2.plot(np.concatenate((t_recovery, t_segments)), np.concatenate((np.zeros_like(MZ_recovery), MXY_segments)), label=tissue_name, marker='o', markersize=1)

ax1.set_xlabel('Time (ms)')

ax1.set_ylabel('$M_Z$ (Longitudinal Magnetization)')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True)

ax2.set_xlabel('Time (ms)')

ax2.set_ylabel('$M_{XY}$ (Transverse Magnetization)')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True)

# Annotations

start_readouts = T_recovery

end_readouts = T_recovery + N_segments * TR

mid_readouts = (start_readouts + end_readouts) / 2

y1_min = ax1.get_ylim()[0]

y2_min = ax2.get_ylim()[0]

y1_max = ax1.get_ylim()[1]

y2_max = ax2.get_ylim()[1]

ax1.annotate('Inversion Pulse', xy=(0, 0), xytext=(20, y1_max * 0.15),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->'), ha='left', va='top')

ax2.annotate('Inversion Pulse', xy=(0, 0), xytext=(20, y2_max * 0.15),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->'), ha='left', va='top')

ax1.text(mid_readouts, y1_max * 0.9, 'Readouts', ha='center', va='top')

ax2.text(mid_readouts, y2_min * 0.5, 'Readouts', ha='center', va='top')

ax1.axvspan(start_readouts, end_readouts, color='0.9', alpha=0.6, linewidth=0)

ax2.axvspan(start_readouts, end_readouts, color='0.9', alpha=0.6, linewidth=0)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()